Carolle Benitah

Born in Casablanca (Morocco), lives and works in Marseille (France)

www.carollebenitah.com

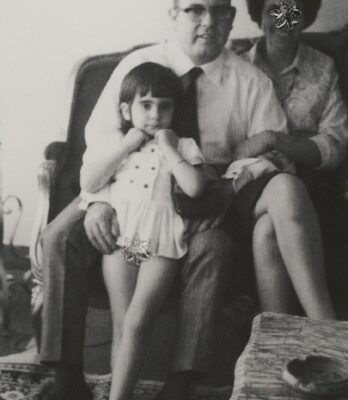

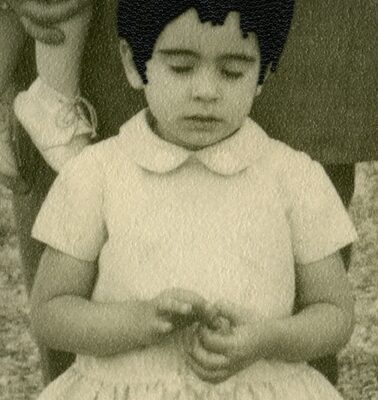

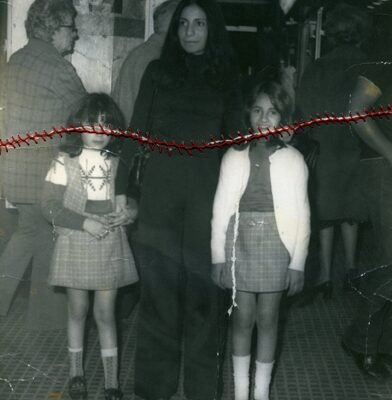

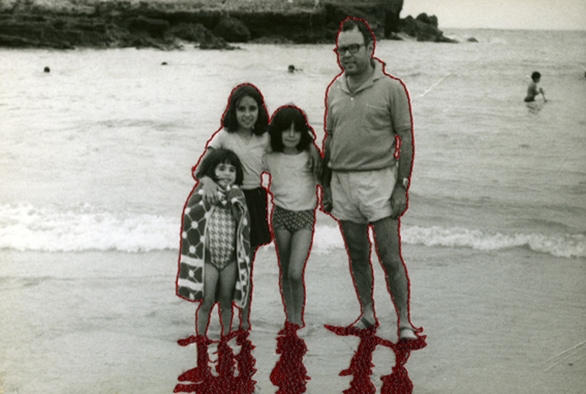

I became interested in my family photographs when, while leafing through the album of my childhood, I was overcome by an emotion whose origin I could not fathom. Those photographs, taken 40 years ago and of which I remembered neither the moment they were taken nor what happened before or after, awoke in me a fear of something both familiar and totally unknown, something of the uncanny discussed by Freud. Those moments fixed on paper represent me, speak of me and of my family, and say things about identity, my place in the world, my family history and its secrets, the fears that shaped me and everything that defines me today.

I decided to explore childhood memories because the process helps me to understand who I am and to define my identity today.

At first, I excavate. Like an archeologist, I unearth family albums and shoeboxes full of pictures, the ones I’m in. I choose snapshots, since they have a connection to memory and loss.

Those photographs are fragments of my past that I interpret from a subjective point of view, like so many confessions. I organize the pictures, digitize them, and print them. I don’t work on the original photograph. I transpose that reality onto a different paper, I sometimes reframe a detail that calls out to me, and I choose my format. The interpretive works begins in those steps.

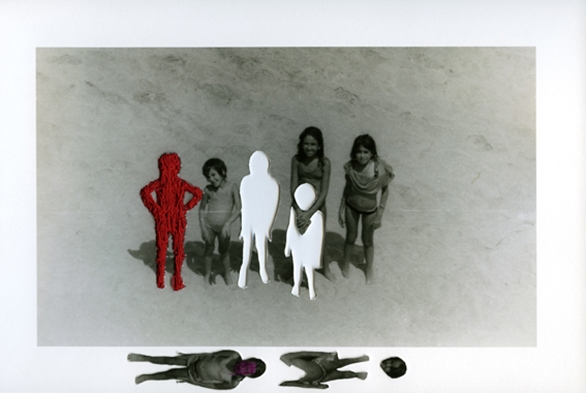

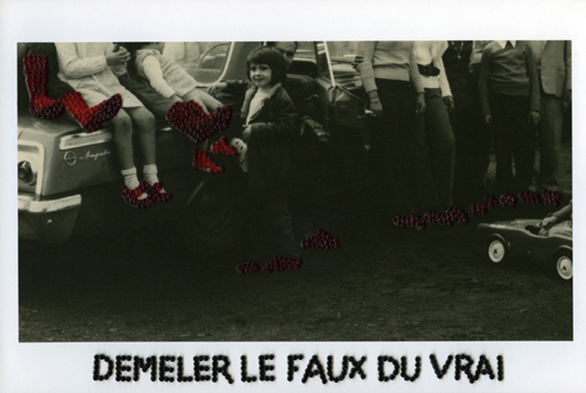

Once I’ve made those choices, I begin telling my version of the facts. I look into my own history, sometimes from a distance of 40 years and with experience that modifies my perception of the events. A human being’s past, as opposed to the remains of some ancient temple, is neither permanent nor complete, but reconstituted by the present. With that in mind, I begin the needlework: embroidery and beading.

Embroidery is a uniquely feminine activity. In the past, the embroiderer was a paragon of virtue. Embroidery and waiting were also intertwined: women embroidered while waiting for their men to return home.

Embroidery occupied a real place in the environment I grew up in. Girls from good families were taught to sew and embroider. It is the activity of perfect women.

My mother embroidered her trousseau.

There is nothing subversive about embroidering, but I corrupt it through my intentions. I use its falsely decorative artifices to reinterpret my history and to denounce its failings. The two activities come together in a form of protest, embroidery–a sign of proper upbringing for a housewife–and the discourse I denounce did not make me what I was supposed to be: a good girl, a perfect wife, and a loving mother.

To embroider my photograph, I make holes in the paper. With each stitch, I stick the needle through the paper. Each hole is a putting to death of my demons. It is like an exorcism. I stab the paper until I don’t hurt anymore.

Each photograph tells its story. Each photograph lifts the veil from the past. It is a story of revelation. It is work related to emotions.

I tell my story about little red riding hood. It is the story of a little girl swallowed by the wolf. Here we are surrounded by stories of transgression, by hemmed in paths not to be overstepped, by disobedience.

I speak of childhood fears. I embroider cockroaches invading the space, but they have angel wings. And the powerful fraternal attachment protects me and saves me.

I use a red thread, which is my connecting thread. It leads me through the maze of my past. Red is the color of violent emotions, the color of blood, of bad blood, it is also a color of sexuality.

The beads chosen for their shininess and their delicacy accentuate the decorative element and create a discontinuity. I reintroduce the gestures of handiwork in this series and renew my connection with my previous work as a clothing designer.

It is a work in three dimensions.

Writing is also involved. It accompanies the photograph. It is like a key to deciphering the mystery.

This slow and precise work is a metaphor for the meticulous manufacture of the self and of time going by.

The family album catalyzes the memory and imagination on which I sew, embroider, paste, and cut. I play with the running red thread of emotions and the fragility of the glass beads, sometimes allowing the archaic ruins of my story to come to the surface. Images of the past and intercession of the present, reality and dream are the keys to my pictorial language.

The needle and thread are there to rearrange the evanescent images of memory.

Mixing marvels and terrors, I reexamine childhood memory even as I update the conscious and unconscious cultural representations of the traditional role of women and of images of the family.